You type a website URL into your browser, hit enter, and the site loads instantly.

Behind that simple action is a system called Domain Name System (DNS) that translates domain names into IP addresses. Without it, you’d need to memorize strings of numbers like 172.217.14.142 just to visit your favorite site.

DNS is what makes the internet usable. It’s also what routes your email, helps protect against spam, and keeps websites loading fast.

When DNS breaks, websites won’t load and your site becomes unreachable. Below we’ll get into what DNS is, how it works, so you can better manage your site (and fix things if it breaks).

Table of Contents

What is DNS?

DNS stands for Domain Name System. It translates human-readable domain names like supporthost.com into the numeric IP addresses that computers use to find each other on the internet.

Think of DNS as the internet’s phone book. Instead of looking up a person’s name to find their number, DNS looks up a domain name to find a server’s IP address.

IP addresses are strings of numbers that identify every device connected to the internet. IPv4 addresses look like 104.19.184.120. While, IPv6 addresses are longer, like 2400:cb00:2048:1::c629:d7a2.

DNS matches domain names to these IP addresses automatically. You type supporthost.com and DNS finds the IP address. Then, your browser connects to the right server.

Before DNS existed, the Stanford Research Institute maintained a file called HOSTS.TXT. It listed every computer on the early internet and its numeric address. As the internet grew, this became impossible to maintain.

Luckily for the fate of the internet, Paul Mockapetris created DNS in 1983 to solve this problem. Instead of one giant file, DNS information is stored across millions of servers worldwide working together.

How DNS Works

When you type a domain into your browser, a DNS lookup starts. Your computer checks two places first, the hosts file and the DNS cache. The hosts file is a text file that maps domains to IP addresses, and the DNS cache stores temporary records of recently visited sites.

If your computer finds the IP address locally, it uses it immediately. No servers need to be contacted, so the site loads faster. If the address isn’t cached, your computer sends a query to a DNS resolver. This is usually operated by your internet provider. The resolver checks its own cache first. If it has recently looked up the domain, it returns the cached address immediately.

When the resolver doesn’t have the answer, it searches through the DNS hierarchy.

First, it queries a root nameserver. There are 13 sets of root servers worldwide. They don’t know your domain’s IP address, but they know which TLD server to ask.

Next, the resolver contacts the TLD nameserver. For supporthost.com, that’s the server handling all .com domains. The TLD server points to the authoritative nameserver for your specific domain.

Finally, the resolver queries the authoritative nameserver. This server stores all DNS records for the domain, including the A record with the IP address.

Then, the authoritative nameserver sends the IP back to the resolver. The resolver sends it to your computer. Your browser connects to that IP address and loads the website. The whole process takes milliseconds.

After completing a lookup, the resolver caches the result. How long it stays cached depends on the TTL (Time to Live) value set by the website owner.

Types of DNS Servers

We gave you an overview of the DNS process above, now we’ll go a little bit more in-depth. There are four types of DNS servers that work together to complete a lookup.

DNS Recursive Resolver

The resolver is the middleman. Your computer sends queries here first. The resolver then searches through the DNS hierarchy to find the answer.

The resolver is like a librarian who finds the book for you instead of just pointing to the shelf. Most people use resolvers provided by their ISP. But you can switch to public DNS services if you want faster or more secure DNS.

Root Nameserver

This is the first stop in the lookup chain. When the resolver doesn’t have a cached answer, it contacts a root server.

Root servers don’t store IP addresses for domains. They maintain a directory of TLD nameservers and point the resolver in the right direction.

There are 13 sets of root servers worldwide (named A through M). They’re distributed across hundreds of physical locations. Your query automatically goes to the closest server.

TLD Nameserver

This manages all domains within a specific top-level domain. There’s a TLD server for .com, another for .org, another for .net, and so on.

When the resolver contacts a TLD server, it learns which authoritative nameserver holds the records for the specific domain.

Authoritative Nameserver

This server stores all actual DNS records for a specific domain. That includes the IP address, mail server info, and other DNS data.

When you own a domain and set up a website, your DNS records live on an authoritative nameserver. This might be run by your hosting provider, domain registrar, or a dedicated DNS service.

The authoritative server sends the IP back to the resolver, which delivers it to your computer. Recursive resolvers search for answers on your behalf. Authoritative nameservers are the final source of truth with the actual records.

DNS Records Explained

DNS records are the actual data stored in the DNS system. They tell DNS servers how to handle requests for your domain.

All records for a domain are stored in a DNS zone file on the authoritative nameserver. When you change DNS settings, you’re editing records in this file.

Each record has a structure with several fields. The name field shows which domain or subdomain the record applies to, the type specifies what kind of record, the TTL determines cache duration, and the rdata contains the actual information.

A Records

This records maps a domain to an IPv4 address. This is the most essential DNS record. When someone visits your site, an A record tells their browser which server to connect to. For example, supporthost.com might point to 104.19.184.120.

You can have multiple A records for load balancing or backups. Most domains have at least two by default. One for the root domain and one for FTP access.

AAAA Records

This works like A records but uses IPv6 addresses instead of IPv4. As the internet transitions to IPv6, these are becoming more common.

CNAME Records

This record creates an alias pointing one domain to another. Instead of pointing to an IP, a CNAME says “this domain goes to the same place as that domain.”

This saves time because you don’t need multiple A records pointing different domains to the same IP address. For example, blog.yourdomain.com could point to www.yourdomain.com via CNAME. If you later change the IP address, you only update the A record for www, and the CNAME automatically follows.

MX Records

This record tells email providers which mail servers handle incoming email for your domain. Without MX records, you can’t receive email at your domain.

Most domains have at least two MX records for redundancy and each includes a priority number. Lower numbers have higher priority, so email tries the lowest number first.

TXT Records

This stores text information about your domain. Originally for human-readable notes, now used for several technical purposes.

Some common uses include SPF records that specify which mail servers can send email for your domain, domain verification for services like Google Search Console, and DKIM/DMARC records for email security.

NS Records

Specifies which nameservers are authoritative for your domain. It also tells the DNS system where to find your DNS zone file.

When you switch hosting providers and change nameservers, you’re updating these NS records.

SRV Records

This provides information about available services, including port numbers and priorities. These records are less common (so you might not have any for your domain) but are important for specific applications like VoIP or instant messaging.

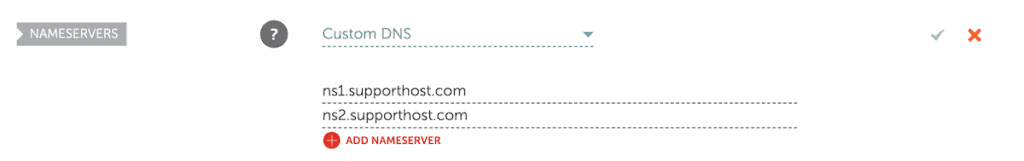

Nameservers and How to Change Them

Nameservers are specialized servers that store all DNS records for a domain. When someone tries to visit your website or email you, the DNS system contacts your nameservers to get the necessary information.

Nameserver addresses look like domain names. Most hosts give you two or more for redundancy.

SupportHost’s might look something like this.

- ns1.supporthost.com

- ns2.supporthost.com

When you register a domain and buy hosting from the same company, nameservers are configured automatically. Your domain uses that company’s nameservers, and your DNS records are created there.

But if you buy your domain from one place and hosting from another, you need to update the nameservers manually.

Here’s a common scenario. You register a domain with one company, but host it with SupportHost. By default, your domain uses the registrar’s nameservers. But your website files are on SupportHost’s servers. To connect them, you’ll need to change your nameservers to SupportHost’s.

You can only change nameservers where you registered the domain. You’ll make the change in your registrar’s control panel.

The process is similar no matter what platform you’re using. All you have to do is log in to your registrar account, navigate to domain management, find the nameservers option, enter the new nameservers your hosting company provides, and save your changes.

Keep in mind, the update doesn’t happen instantly. DNS propagation takes time to spread the changes across the internet. More on that next.

DNS Propagation

DNS propagation is the time it takes for DNS changes to spread across all DNS servers worldwide.

When you modify DNS records or change nameservers, the update doesn’t happen everywhere at once. Millions of DNS servers worldwide have cached the old information. Every server needs to update its cache with the new data.

Different servers will update at different times based on when they last queried your domain and your TTL values. If your A record has a TTL of 14400 seconds (four hours), DNS servers cache it for four hours before checking for updates.

Propagation can take anywhere from a few minutes to 48 hours. Usually, most changes are completed within a few hours.

During propagation, different visitors might see different versions of your site. Some get directed to the new server while others still reach the old one. This happens because some DNS servers have been updated while others haven’t.

Your site typically stays accessible during propagation. Users can still visit, though they might see content from the old server or the new one.

If you want your site to propagate faster, then you can lower the TTL value. If you know you’ll be making DNS changes soon, reduce the TTL a day or two in advance to something like 300 seconds (five minutes). After that propagates, make your actual changes, and servers checking every five minutes will spread your updates much faster.

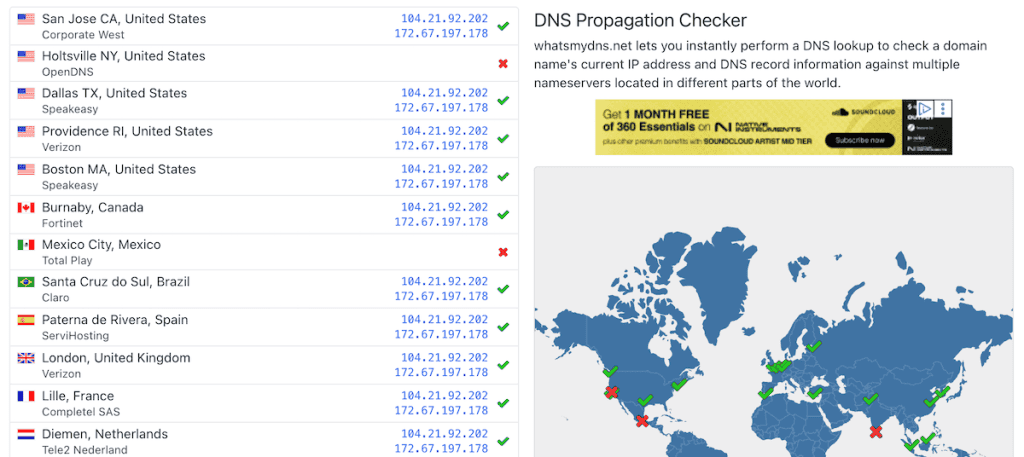

You can always check propagation status using tools like WhatsMyDNS. Enter your domain and select the record type you changed. The tool queries DNS servers in various countries and shows which locations see the old info and which see the new.

DNSSEC

Domain Name System Security Extensions (DNSSEC) adds security to DNS by protecting against attacks where hackers redirect your traffic to malicious servers.

Traditional DNS has no way to verify that responses are authentic. An attacker could intercept a query and send back a fake response directing you to a malicious server. This is called DNS spoofing or cache poisoning.

DNSSEC uses cryptographic signatures to verify that DNS responses are legitimate. When you query a domain with DNSSEC enabled, the system checks the digital signature. If it matches, the response is authentic. If not, it’s rejected, and you see an error instead of connecting to a potentially malicious server.

DNSSEC creates a chain of trust from root nameservers down to individual domains. Root servers have a public key that verifies TLD signatures, TLD servers have keys that verify authoritative nameserver signatures, and each level can verify the level below it.

Not all domains use DNSSEC. Enabling it requires support from both your registrar and DNS provider, and while some make it easy with one-click activation, others don’t support it at all.

Availability depends on your specific TLD and where your domain is registered. Check with your hosting provider to see if DNSSEC is available. For most site owners, DNSSEC provides extra security but isn’t critical. SSL certificates, strong passwords, and keeping software updated are typically higher priorities.

Managing DNS Records

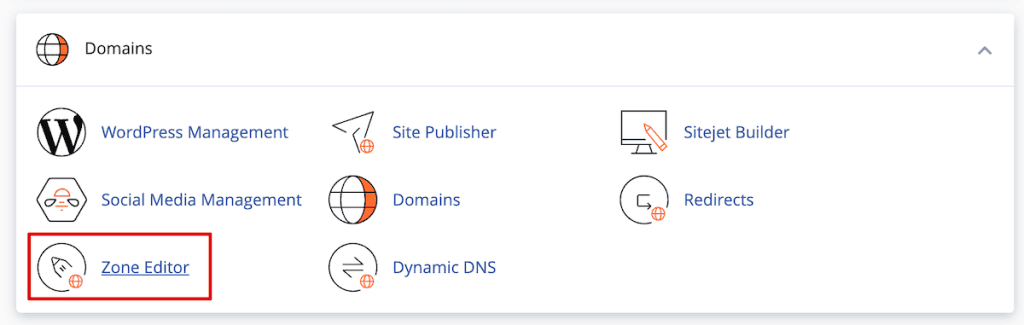

Managing DNS records is easy with most hosting control panels. Most include a DNS zone editor for viewing and modifying your records. SupportHost customers access the DNS Zone Editor through cPanel. Simply login to cPanel, navigate to your domain, and find the Zone Editor in the Domains section.

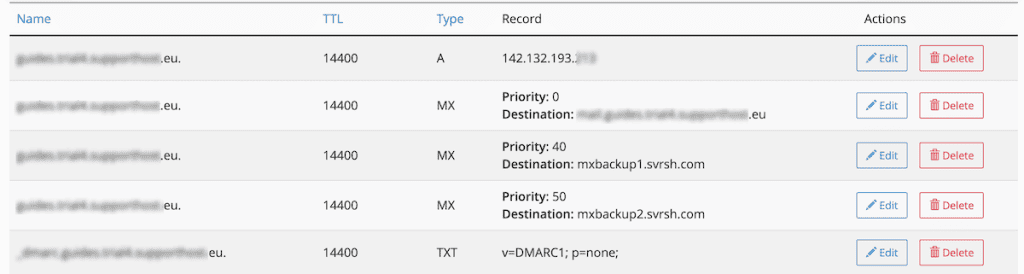

The editor displays all current records in a table. You’ll see each record’s type, name, and value. Most hosts create default records when you set up your domain, including A records for your main domain and www subdomain, plus MX records if you’re using their email. Simply click Edit to make changes to any existing record. Be careful when deleting records, especially NS and MX records, since removing critical DNS records can break your website or email.

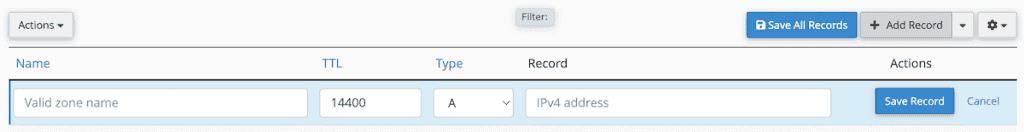

To add a record, click the Add Record button. Then, enter the Name, TTL, Type, and Record.

For an A record, enter the hostname (often @ for your root domain, or a subdomain name like “blog”) and the IP address. If you don’t know the IP, your hosting provider can give it to you. TTL determines how long servers cache the record, and most providers default to 14400 seconds (four hours). You can usually leave this alone unless you have a specific reason to change it.

Other record types follow similar steps. For CNAMEs, enter the subdomain and target domain. For MX records, enter the mail server address and priority number.

Common DNS Problems and Fixes

DNS issues can prevent your site from loading or cause email problems. Here are some of the most common DNS issues you might experience.

DNS Server Not Responding

This error appears when your computer can’t reach a DNS server. The problem might be your internet connection, DNS settings, or the DNS servers themselves.

First, check if other websites load. If they do, the issue is specific to one domain. If nothing loads, your DNS resolver might be down. To fix this, flush your DNS cache to clear corrupted or outdated information.

On Windows, run the following: ipconfig /flushdns

On Mac, run the following: sudo dscacheutil -flushcache

If it’s still not working, then try changing your DNS servers. Your computer probably uses your ISP’s DNS. You can switch to a public DNS service instead.

Propagation Delays

If you recently updated DNS records or changed nameservers and your site won’t load, then propagation might still be in progress.

Start by checking status using WhatsMyDNS (shown above). If different locations show different results, then propagation is ongoing, and try waiting a few more hours.

If propagation seems complete but your site still doesn’t work, then double-check that you entered the DNS info correctly. A single typo in an IP address or nameserver breaks everything. Review your records and compare them to what your hosting provider gave you.

Incorrect DNS Records

If your A record points to the wrong IP address, then visitors get directed to the wrong server. If MX records are wrong, then email doesn’t work.

Double-check all records against information from your hosting company or email service. Make sure nameservers are spelled correctly, IP addresses are accurate, and MX records have the right priority values.

Cached Outdated Information

Sometimes DNS works fine globally, but your computer has cached old information. To fix this, flush your local DNS cache (using the commands above) and clear your browser cache. Browsers sometimes store DNS info separately from your operating system.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between DNS and nameservers?

DNS is the entire system that translates domain names to IP addresses. Nameservers are specific servers within that system that store DNS records for your domain.

How long does DNS propagation take?

Typically between a few minutes and 24 hours, though the official estimate is up to 48 hours. Most changes propagate within 4-6 hours.

Can I use Google’s DNS servers instead of my ISP’s?

Yes. You can change your computer’s DNS settings to use any public DNS service. These often provide faster resolution and better security.

What happens if DNS fails?

You won’t be able to access websites using domain names. You could still visit sites by typing IP addresses directly, but most people don’t know IP addresses for the sites they want. Email would also fail because mail servers rely on DNS.

Do I need DNSSEC for my website?

DNSSEC provides additional security, but it isn’t essential for most sites. If your site handles sensitive data or financial transactions, DNSSEC adds extra protection. Check with your hosting provider about availability.

Closing Thoughts: What is DNS?

DNS works invisibly every time you visit a website, send an email, or use an app. It translates domain names to IP addresses, so you don’t need to memorize long strings of numbers. Basically, it makes the web more usable.

Understanding DNS helps you make better decisions about your website. You’ll know how to change hosting providers, set up email correctly, and troubleshoot problems when they occur.

The core concepts around DNS are simple: domains get translated to IP addresses through servers working together, records store different types of information, and changes take time to propagate globally.

Now you’re well equipped to manage your domain and website with confidence.

Do you have questions about DNS or run into issues setting it up? Drop a comment below.

Ready to build your WordPress site?

Try our service free for 14 days. No obligation, no credit card required.